- Home

- Steve Schafer

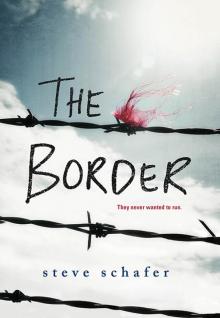

The Border

The Border Read online

Thank you for purchasing this eBook.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading!

SIGN UP NOW!

Copyright © 2017 by Steve Schafer

Cover and internal design © 2017 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover branding by Kerri Resnick

Satellite imagery map on p. 347 © Google 2017. Used by permission.

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Contents

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

La Quince

Where to Go?

Finding Purgatory

La Frontera

On Edge

Sonoyta

Coyotes Are Dogs

Out of Options

Bonded by Blood

Walking Blind

Two by Two

Beneath the Willow

Mota

Pollitos

A Familiar Face

Promises

Vultures

Perspectives

Moving On

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Back Cover

For Sydney and Tyler

La Quince

The car looks suspicious. I can’t put my finger on why, but I can’t stop staring at it either.

We’ve just arrived at my cousin Carmen’s fifteenth birthday party—her quinceañera. The street is already lined with vehicles. It’s nearly dusk, and we’re late. We always are. That’s my dad, always behind and fine with it.

We park our truck in front of the small driveway, blocking it. My dad gets out, tucks the keys behind the rusty gas tank cover, and opens my mother’s door. He takes her hand and helps her out, then strolls toward the house as though we’re ten minutes early.

I follow.

“I have a surprise for you tomorrow, Pato,” my dad says.

I’m not looking at him. I peer at that car parked on the street, a few houses away.

The rear bumper. That’s it.

It’s an older car, the kind that normally has a chrome bumper. But this one has been painted a dull, matte black, like the rest of the car.

Weird.

“It’s not really a surprise,” my mom says.

“Wait, what surprise?” I ask.

“Pato is going to be disappointed if you call it a surprise,” she says to my dad. “Surprises are good. This isn’t. It’s not bad, mi amor. But it’s not a present.”

I’m listening to my mother but still staring at the car. A pair of eyes meets mine in its side-view mirror.

Someone is in the car. Why is he just sitting there?

“Okay, Pato. It’s not a surprise—it’s news. It’s a change. A good change,” my dad tells me.

“What kind of change?”

I look from the car to my dad. I like routine. I have a way of doing things, and I like to stick to it.

“Tell you what. We’ll talk about it tomorrow, okay?”

As we near the house, I can see the car from a different angle. The hubcaps are painted black too. Bumper to bumper, the entire car is black. And on the back door, I see a small dent.

No, not a dent. Is that a bullet hole?

I squint. It’s hard to tell. But I can see the silhouette of the driver. He blows a thin stream of smoke out the window.

I glance at my parents to see if they notice, but they’re too wrapped up in each other and all this talk about change.

Then a head pops up in the back seat and drops back down from view.

Did I imagine that?

I stare. There’s no movement.

“Hey, Pato. Are you okay?” my mom asks as we arrive at the door.

“Yeah, it’s just—” The door opens before we knock.

“Look who finally decided to show up!” My aunt opens her arms wide to hug my mom, while my uncle greets my father with a drink. Beyond them stands Arbo, my cousin and best friend.

As we step inside, I turn back toward the car. The driver’s head rotates. It’s too dark and too far away to see any kind of expression. But somehow it feels threatening.

The front door closes behind us.

• • •

I think about mentioning the car to Arbo. Just a passing comment. He would know what to do with it—to pay attention or let it go.

Hey, there’s some creepy guy in a car sitting outside your house.

But the words never make it to my lips. He grabs the conversation before I do.

“You’ve got to see Carmen. I didn’t even recognize her.”

“It’s a quince. They’re supposed to get all spiffed up,” I say, though that’s putting it mildly. Teenage girls are notorious for going overboard for their quinceañeras.

“I know. It’s just weird to see my little sister with cleavage. I don’t like thinking about how other people might be looking at her.”

I can’t imagine Carmen like that either. She’s only one year younger than Arbo and me, but I still think of her as my little cousin.

“Like who?” I ask.

Arbo scans the backyard. His house sits along the edge of town. While the house itself is small, the backyard is not. One advantage of bordering the Sonoran Desert? Full access to a swath of otherwise unwanted land.

“Like that guy,” he says, pointing to the other side of the yard.

Marcos.

Marcos is one year older than us and about three years cooler. At our high school, he’s famous. He scores the goals. He gets the girls. For us—or for me, at least—his life seems like a fantasy. I know of him more than I actually know him.

Marcos catches our gaze and gives an acknowledging nod. Then he turns to look at the small group of girls gathered next to Carmen.

True to form, the girls teeter on too-high heels, engulfed by lavish dresses studded with sequins and beads, their faces hidden behind too much makeup. All are nearly unrecognizable from their normal selves except one: Marcos’s younger sister, Gladys, who is the same age as Carmen.

Amid the quinceañera extravagance, she’s understated, like she’s not even trying. If she’s wearing makeup, I can’t tell. Her dress is simple. It looks homemade, but n

ot in a bad way. There’s nothing flashy about her, but she shines. I’ve noticed her before, though never quite like this.

She looks at me for a second, then her eyes dart away.

“¡Una foto! A picture!”

I’m pulled out of my thoughts. Arbo’s dad and my dad are arm in arm and waving for us to join them. They’re brothers, best friends, and business partners. They share ownership of the truck we drove here this evening. Like Arbo and me, they do nearly everything together.

Arbo and I cram into the space between them, their arms stretching across our backs, embracing us.

“To partners!” they say, smiling wide for the camera.

They have it in their minds that one day Arbo and I will join their construction company, and the four of us will be partners. It’s a small business. They don’t have any regular employees, only a few people they pay by the day when they need an extra hand. But for a couple of guys who were working in the fields and factories several years ago, they’re living a dream.

The camera flashes, and I imagine another picture, years from now, with a third generation of partners sandwiched between Arbo and me. My smile lingers beyond the flash. Who knows?

I look around the party. They must be doing well. In Mexico, a country of haves and have-nots, we’re definitely the latter. But it doesn’t feel that way tonight. The backyard is a spectacle. Hundreds of colored lights stretch across the sky like stars. Crystal vases filled with dense bouquets in a dazzling array of colors sparkle. A five-person band weaves through the yard, its harmonies surely carrying far out into the barren distance. And near the door where the house opens to the backyard, an ice sculpture sits atop a silken tablecloth. We live in a desert!

The band transitions from one song to the next. In that gap, I hear the roar of a loud engine on the street. For a second, I think back to the car.

Then Arbo says something. And the band resumes playing. My father whisks my mother to the dance floor. Then my uncle stops everything to give a teary speech about Carmen. Everybody toasts. And the celebration marches on into the warm July night.

• • •

“Hey, Pato, let’s go have a smoke,” Marcos says to me, as if it’s more an instruction than an invitation. I’m flattered that he’s asked me, even though I know his options are limited. His family is friends with my family. Otherwise, this isn’t his crowd.

“Okay. Why not?” I’m not a smoker, but I have tried it before.

I motion for Arbo to join us.

A weathered adobe wall encloses the yard, separating the house from the desert. We quietly exit through a gap in the back wall where there was once a gate. Beyond it is a blazed landscape of jagged rocks, wiry weeds, all shapes of cacti, and a host of clumpy plants that pass as bushes. It’s an uninviting place. Almost everything that exists here—other than the sand—is some combination of dry, prickly, and short.

We walk along the wall, which leads to a trail that snakes through the maze of spiny plants, made visible by the faint glow of a new moon and light from a few nearby houses. Halfway down the path, I notice that Gladys is on our heels, following in silence.

We arrive at an opening in the brush about 150 meters from the house. There, in the middle of nothing, lies the back seat of a car—a long, plastic bench seat. I don’t know what kind of car it belonged to, and I don’t know how it got here, but I still know it well. I’ve been out here many times before. It’s one of my favorite places in the world. Two years ago, I had my first kiss here. I was so nervous, I accidentally tipped the bench backward, and we both tumbled head over heels. This bench outlasted that relationship. Every August, this is my front-row seat for an annual meteor shower. And it’s perfect anytime for watching the stars that don’t fall. Arbo and I have passed many hours here staring into the cosmos in awe.

Gladys and Marcos sit on the bench, settling into the grooves where crooked springs don’t poke in the wrong places. Marcos holds out the pack of cigarettes. Arbo and I each grab one, then take a seat in the dirt, facing them. Gladys chooses not to smoke, either out of respect for her older brother or because she has better sense than the rest of us.

I’ve come to realize that there is a gap between doing something to look cool and actually looking cool while doing it. I hit puberty late. Very late. About a year ago. And it defines me now. My voice cracks. I’m pimpled. I have body parts that seem to have a mind of their own. Seldom do I look cool doing anything, let alone drawing smoke down my throat. It’s itchy and awful tasting. My only consolation is Arbo, who is doing a brilliant job of attracting attention, so it’s not on me. He coughs out a wispy stream of smoke, which rises with the lingering desert heat into a faint cloud above our heads, slowly bleeding into the sky. We laugh.

“Th-top,” he says amidst a flurry of hacks. Arbo lisps when he gets flustered.

“Ooh, th-top, pleathe th-stop!” Marcos waves his arms in the air with an exaggerated flair.

Again, we laugh.

Arbo dials up his disapproval, though I can tell he’s playing along. He likes the laughs as much as we do, even when they’re at his own expense.

Gladys looks at me with a shy smile. And for an instant, this moment is perfect.

Then we hear a shot.

I recoil. All noise stops.

We look at one another around our circle. Their confused expressions mirror my own. Arbo starts to voice the same hope I have: “Firecrack—?”

He doesn’t finish.

He’s interrupted by a second shot and the screams that follow. Soon the blasts are indistinguishable, and the cries unimaginable.

Arbo stands to move in the direction of the house, but Marcos latches onto his belt, yanking him back down to the dirt with a firm “No!”

“What are you doing?” Arbo shouts.

“Shut up and get down!”

I stay frozen—from shock, from fear, from having no idea what to do. You read about outrageous situations in books and daydream about being the hero, and then you find yourself there, trembling like a coward in the darkness. Nothing prepares you for a moment like this.

I don’t know how long it lasts. Time isn’t moving the same. It’s both the longest and briefest stretch of my life.

Then, as abruptly as it started, the gunfire ends. A sinister silence follows, pierced by what sounds like a fleet of tires peeling.

The car.

I knew something wasn’t right.

Arbo rockets to his feet again, this time quicker than Marcos’s reach. He charges toward the house.

I stay put. Not for fear of what might be in the backyard, but for fear of what I know is there. The screams all stopped for a reason.

“¡Cabrón!” Marcos curses under his breath. His forehead buckles in wrinkles large enough to cast shadows in the moonlight.

Arbo’s heavy footsteps fade down the trail. He makes it about halfway to the house before Marcos sprints into the darkness.

A few seconds later, Gladys and I relent and follow. I don’t know why. We just do.

Ahead, Arbo disappears around the wall into the backyard. “No!”

Marcos’s shadowy outline freezes. Then he turns from the entrance to the backyard and races along the wall toward the front of the house.

I don’t know whether to follow Arbo or Marcos, so I do neither. I stop when the desert trail meets the corner of the wall. Gladys crashes into my back.

Marcos has already disappeared. The entrance to the backyard is paces away, and I can hear Arbo wailing.

My body goes stiff. I don’t want to see what he’s seeing. I don’t want to scream like he’s screaming. I want to go back to when I first saw that car. I should have said something! Why didn’t I say something? I could have stopped this. All I had to do was open my mouth.

Gladys pushes into my back and tugs at my shirt, giving directions as conflicting as what�

�s happening inside my head.

I take a slow, cautious step along the wall toward the entrance. Then another. Gladys clings tighter the closer we get, adding resistance, so each step takes that much more effort.

Step.

Step.

“Stop right there!” shouts an unfamiliar voice from inside the backyard.

Arbo shrieks.

“Where did you come from?” booms the voice.

I slide forward and peer around the wall. Arbo is lying on top of his father’s body, his arms outstretched, as if protecting both of them.

The man advances toward Arbo, gun pointed, finger on the trigger, ready to fire.

“Please!” Arbo lifts his hand like a shield.

“I said where did you come from, hijo de puta!”

“The bathroom! The bathroom!”

The man looks back toward the house, as if questioning Arbo’s answer. I inch further out to get a better view, until the gunman spins in our direction. I yank my head away and stop breathing, terrified he’ll hear my gasps. I can feel Gladys—still pressed against my back—do the same.

Silence.

I listen for any sound—steps, whispers, anything.

Nothing.

“Well,” he says to Arbo, “you came out too early.”

Arbo whimpers.

I peek around the wall again and watch the gunman shrug his shoulders with indifference.

Arbo presses his face flush against his father’s forehead. The gunman places the muzzle on the back of Arbo’s head.

Everything in me tightens. I’ve never felt so helpless.

“I’m sorry, Dad. I’m so sorry,” he sobs, barely audible.

The man rotates the weapon, back and forth, sweeping in slow circles along Arbo’s head. The corners of his mouth drift upward. He’s taunting Arbo. Taunting a boy who is lying on top of his dead father.

This is the Mexico we read about in the paper. We’re all aware of the violence that surrounds us, but it seems more like wild lore, because it hasn’t happened to us. It’s on the front page of newspapers, not in our own backyards.

Until now.

Do something.

Anything!

The Border

The Border